Amelia B. Edwards: Artist and Egyptologist Made Art in the Service of Science

What Edwards drew in 1874 made her a pioneer and advocate for the research and preservation of antiquities.

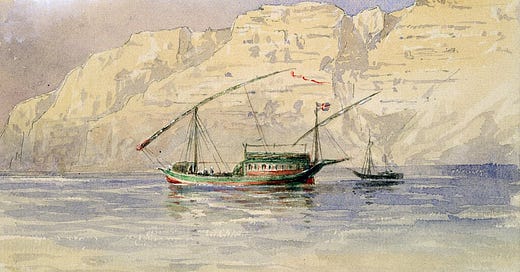

In the late 1800s, English novelist and journalist Amelia B. Edwards (1831-1892) traveled up the Nile River with six other remarkable, Victorian-era women. From her journal writing and on-the-spot sketches, she published a book, “A Thousand Miles up the Nile” (1877), that would change not only her path in life but also help preserve history.

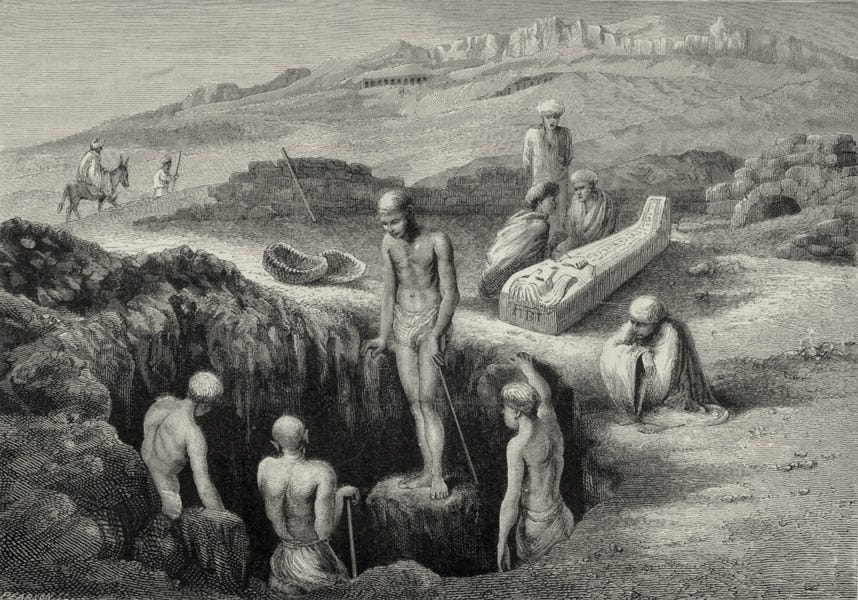

Edwards was already a successful novelist and poet by the time she made this journey. Most of these Ladies of the Field were archaeologists, looking to study Egyptian history through its antiquities. But Edwards was the artist who would document it all. She made over 70 drawings of landscapes, archaeological digs, artifact and hieroglyphics studies, tomb maps and more, with art in the service of science. As was the custom at that time, these drawings were converted by another artist to wood engraving for printing in the book.

She made watercolors at the Abu Simbel Temples, built in the 13th century BC, by Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II, in southern Egypt. The giant limestone figures would eventually be relocated above the rising waters of the man-made Lake Nasser in 1964, before the building of the Aswan Dam.

Edwards wrote like an artist not a scientist.

“Nothing in Egyptian sculpture is perhaps so wonderful as the way in which these Abu Simbel artists dealt with the thousands of tons of material to which they gave human form. The colossi are a triumph of treatment. Side-by-side they sit placid and majestic.”

Edwards witnessed thefts and the physical destruction of many ancient sites. As a result, upon her return to London she set out to hinder these destructive practices through the publication of her book and through speaking tours. With the aim of raising public awareness and encouraging ethical archeology, she became an advocate for research and preservation of antiquities. She co-founded the Egypt Exploration Society with Reginald Stuart Poole of the British Museum. From then on she was known as the "Godmother of Egyptology."

"Shocked at first, they denounce with horror the whole system of sepulchral excavation, legal as well as predatory; acquiring, however, a taste for scarabs and funerary statuettes, they soon begin to buy with eagerness the spoils of the dead; finally, they forget all their former scruples, and ask no better fortune than to discover and confiscate a tomb for themselves. " - from “A Thousand Miles Up the Nile” by Amelia B. Edwards

The Great Sphinx at Giza, near Cairo was carved from a single mass of limestone, around 2500 BC. Edwards drew this mysterious statue, a creature with the head of a human and the body of a lion. Like many others, she wondered about this perplexing juxtaposition, and its hidden tunnels and inscriptions.

We can only imagine what Edwards herself pondered. While others were pillaging, her travel writings and drawings were only taking the story of science and history. Did she feel that her writings and sketches would be part of the scientific record, and also help inform people of this devastation?

Can your own travel journaling and drawing effect change? Answer using the comments section below.

More Resources:

Here’s a full list of the chapters in ‘A Thousand Miles up the Nile’, as well as a list of the illustrations.

This is so interesting what a brilliant woman she was. I love stories of fearless, pioneering Victorian women. 💥