Käthe Kollwitz: A Weavers’ Revolt

Showing compassion and beauty in hardship and suffering

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) made art of deep emotion. She was a remarkable German artist who fearlessly confronted the human condition, particularly that of bereaved mothers, ailing children and the suffering of the working class. Kollwitz experienced her own profound grief at losing her son in World War I. The pain and the guilt she felt for not protecting him is translated into her many drawings, paintings and lithographs.

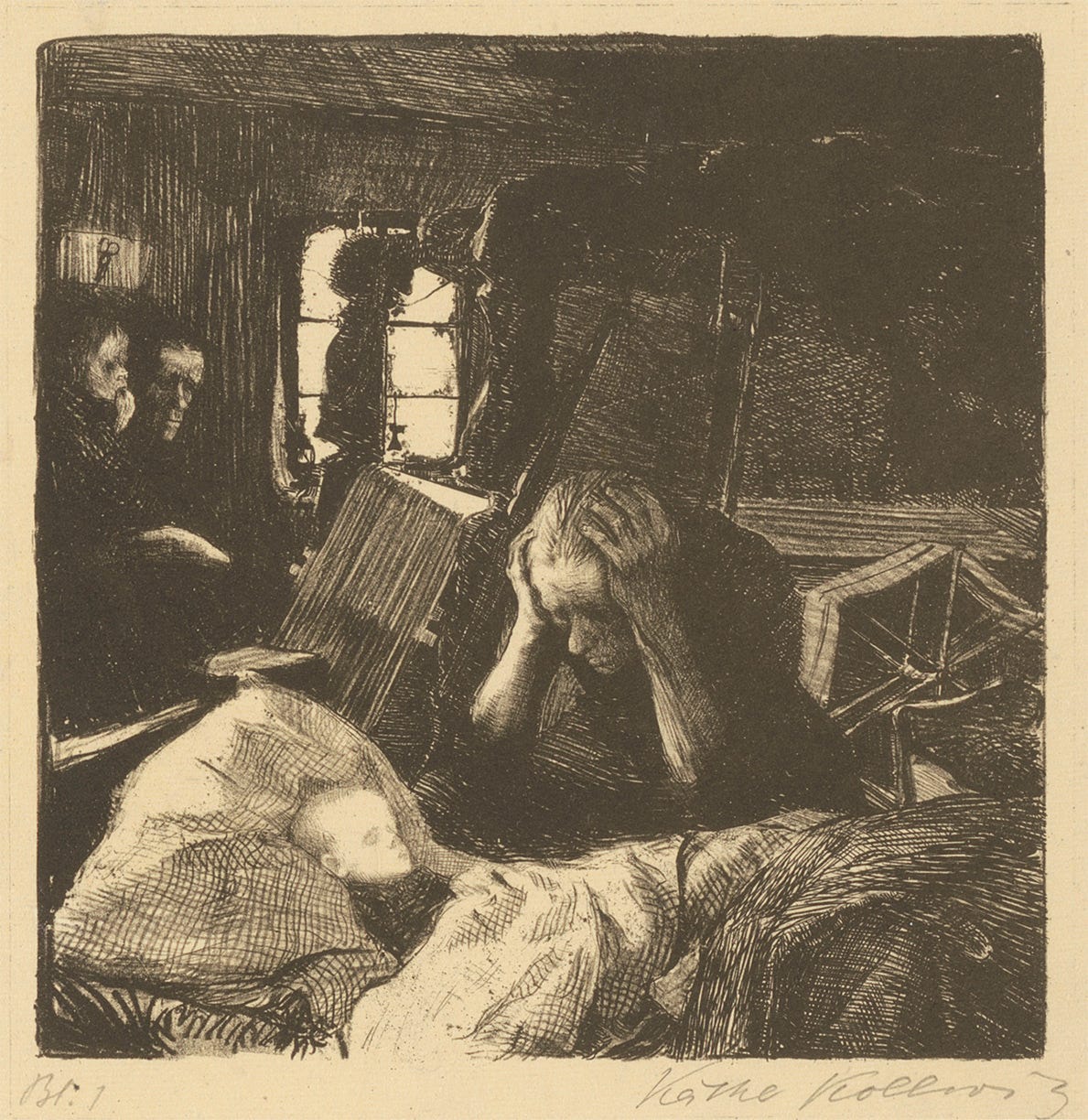

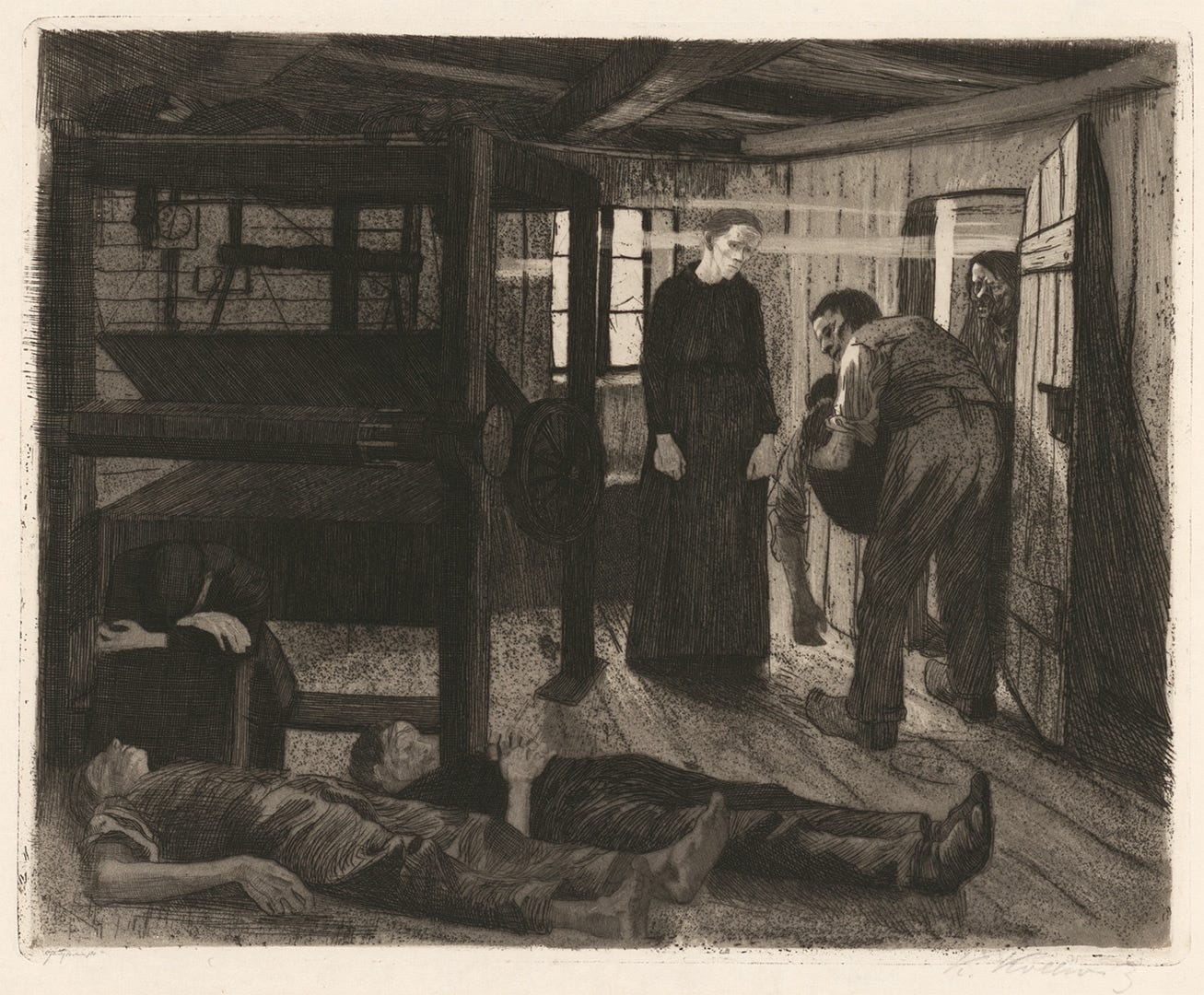

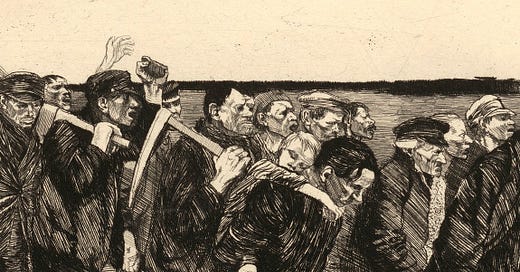

But before that, in 1893, Kollwitz produced a series of prints called Ein Weberaufstand (A Weavers’ Revolt) that was more journalistic, yet delivered a depth of feeling to an historical event. They show how unafraid she was to depict the poverty and vulnerability of children, the plight of impoverished workers and their fight for justice, and the brutal consequences of resistance. These were consistent themes in all of her life’s work.

Her images present the story of a group of Silesian weavers who staged an uprising in 1844, as they revolted against extremely low wages and poor working conditions.

In 1893, Kollwitz was inspired by Gerhart Hauptmann's play The Weavers, in which workers decide their situation is intolerable and rally at the mansion of their employer, who then called in the military. During the protest a stray bullet kills an old man who had opposed the uprising.

Kollwitz’s illustrations are sequential. The first print tells us what led to the revolt. In the second the weavers plan the uprising. In the remaining prints we see the subsequent outbreak and breakdown of their protests. It was newsworthy narrative to share with those unfamiliar with the event. It also presented the universal struggles many workers faced at the time.

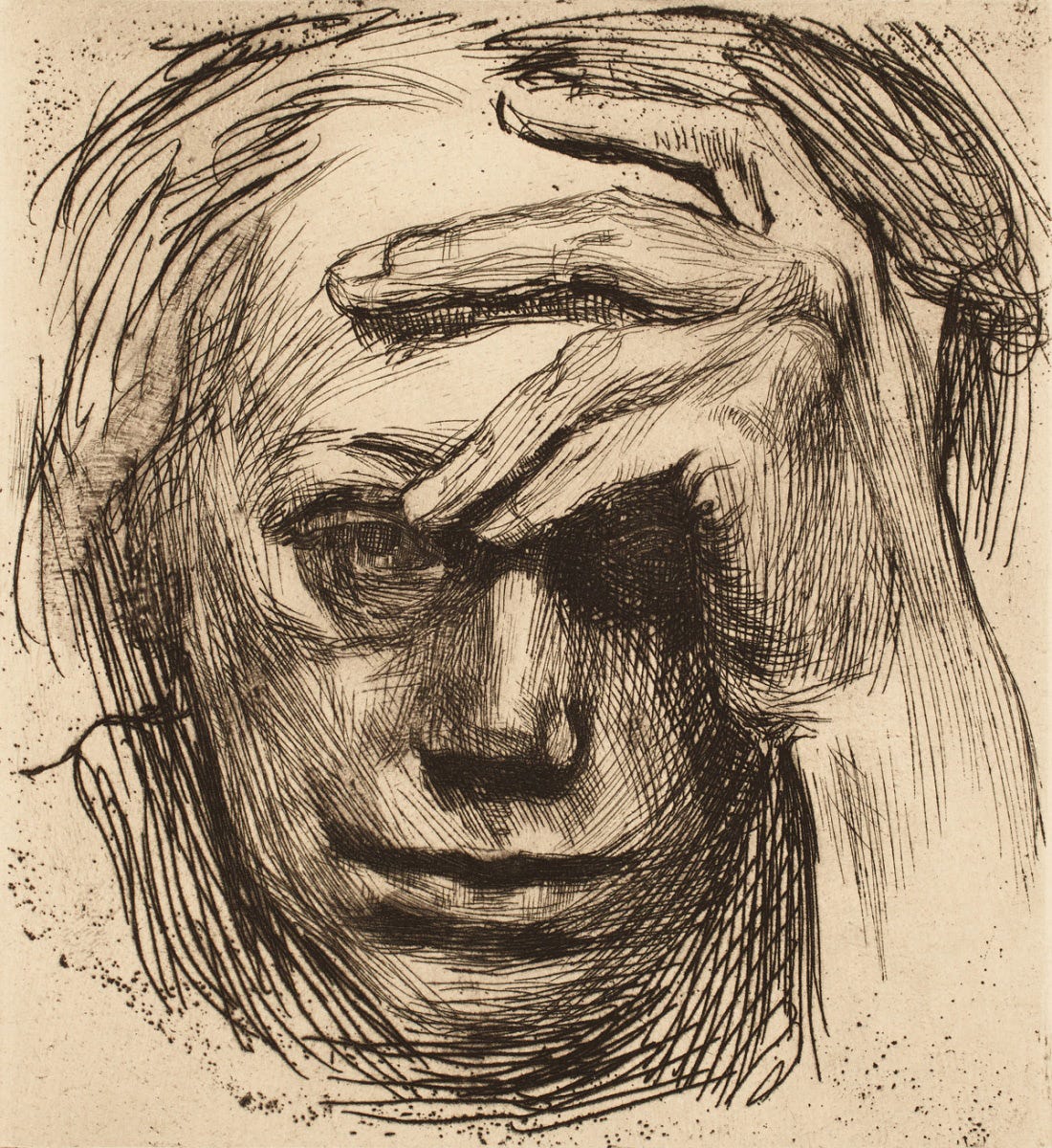

Kollwitz creates complex compositions of figures. Her dense line work delineates the discord of the conflict itself. The chiaroscuro (light and shadow) that is cast over forms give the pictorial presentation its emotional power.

Her etchings and lithographs were put on public display in Berlin in 1898, and was regarded by the authorities as an incitement to class-hatred. Yet their mass publication became a commercial success, that won her national recognition and established her as the artist of the downtrodden.

Käthe Kollwitz’s art speaks to the deep pain and struggles faced by many. She had a unique vision that focused on the marginalized and working class, that challenged the status quo in a male-dominated art world. Despite her own personal grief, she used her talent to share the universal wounds of humanity, giving a voice to the voiceless and shining a light on empathy and resilience.

What can visual journalists today learn from the work of Käthe Kollwitz? Perhaps we shouldn’t shy away from showing compassion and empathy in our work. I think it would make the stories we tell more vivid, honest and beautiful.

‘I would like to emphasize more that compassion and commiseration were at first of very little importance in attracting me to the representation of proletarian life; what mattered was simply that I found it beautiful.’

- Käthe Kollwitz

Hands in Art:

Käthe Kollwitz gave hands a special prominence in her imagery and used them as an expressive device. Hands can be imbued with emotion, character and movement. They can help tell a story. Famed art teacher and artist George Bridgman suggested that while we often train our faces to hide thought and feeling, our hands respond unconsciously to mental states and reveal what the face conceals.More to Know:

More Kollwitz images and preparatory drawings with in-depth commentary can be found on the website of the Käthe Kollwitz Museum, Cologne, Germany.

Thanks for putting Kathe’s story in your feed. She is an incredible artist and continues to be an inspiration. Would love to see a joint show combining her work and the work of Dorothea Lange.

Deeply beautiful, thank you.