Robert Ripley: Believe It or Not!

A passion for travel, adventure, wonder and weirdness

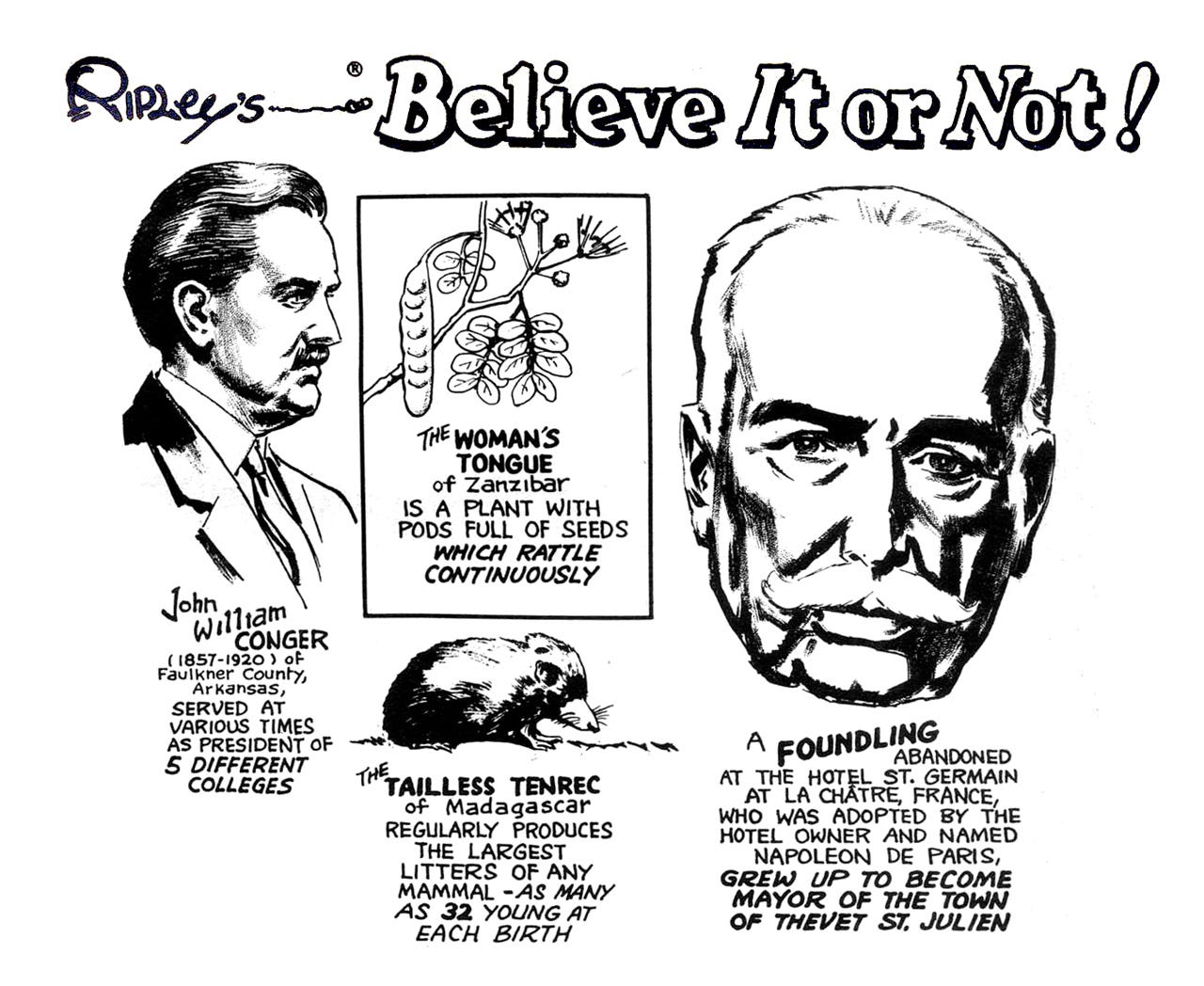

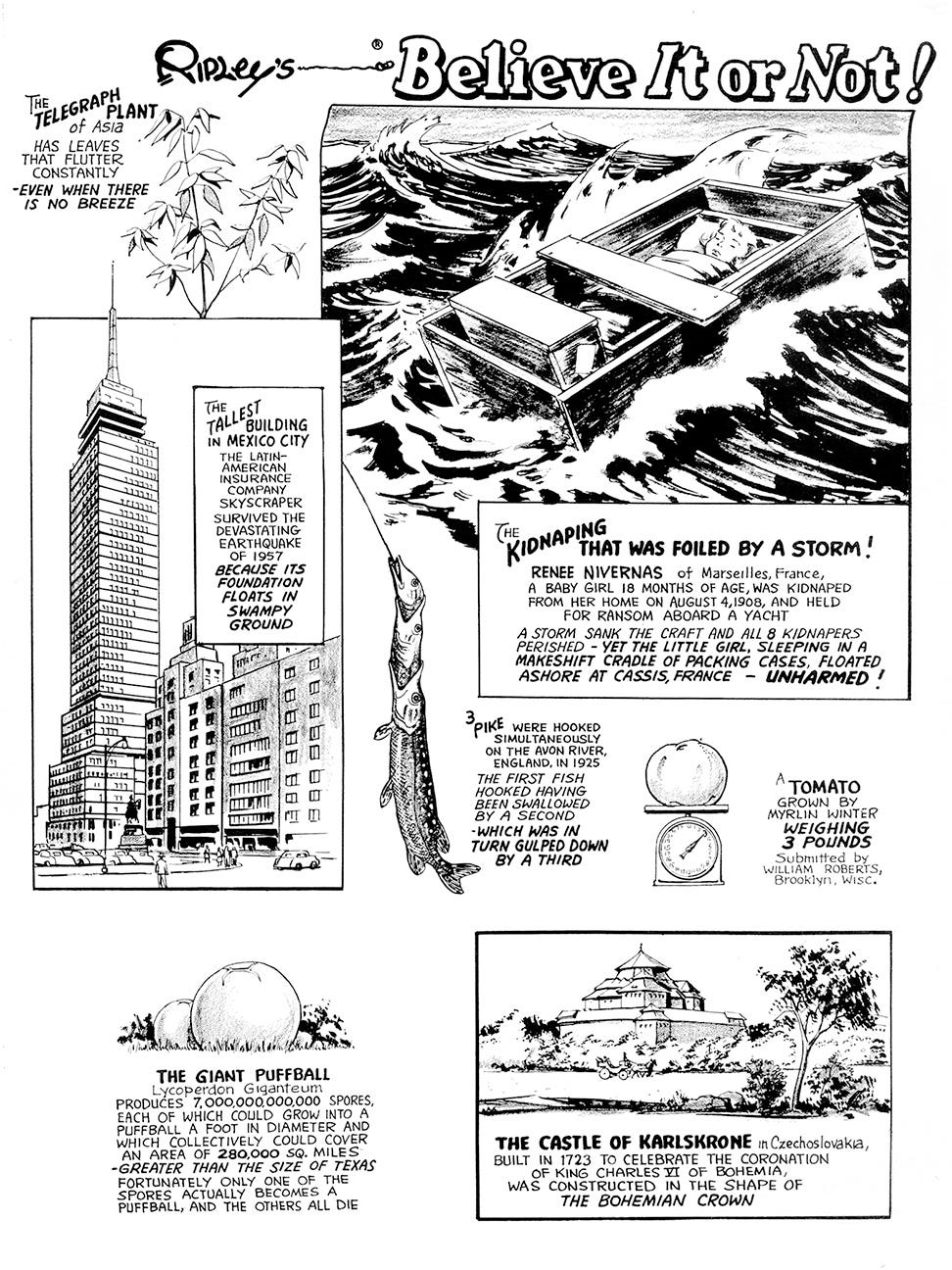

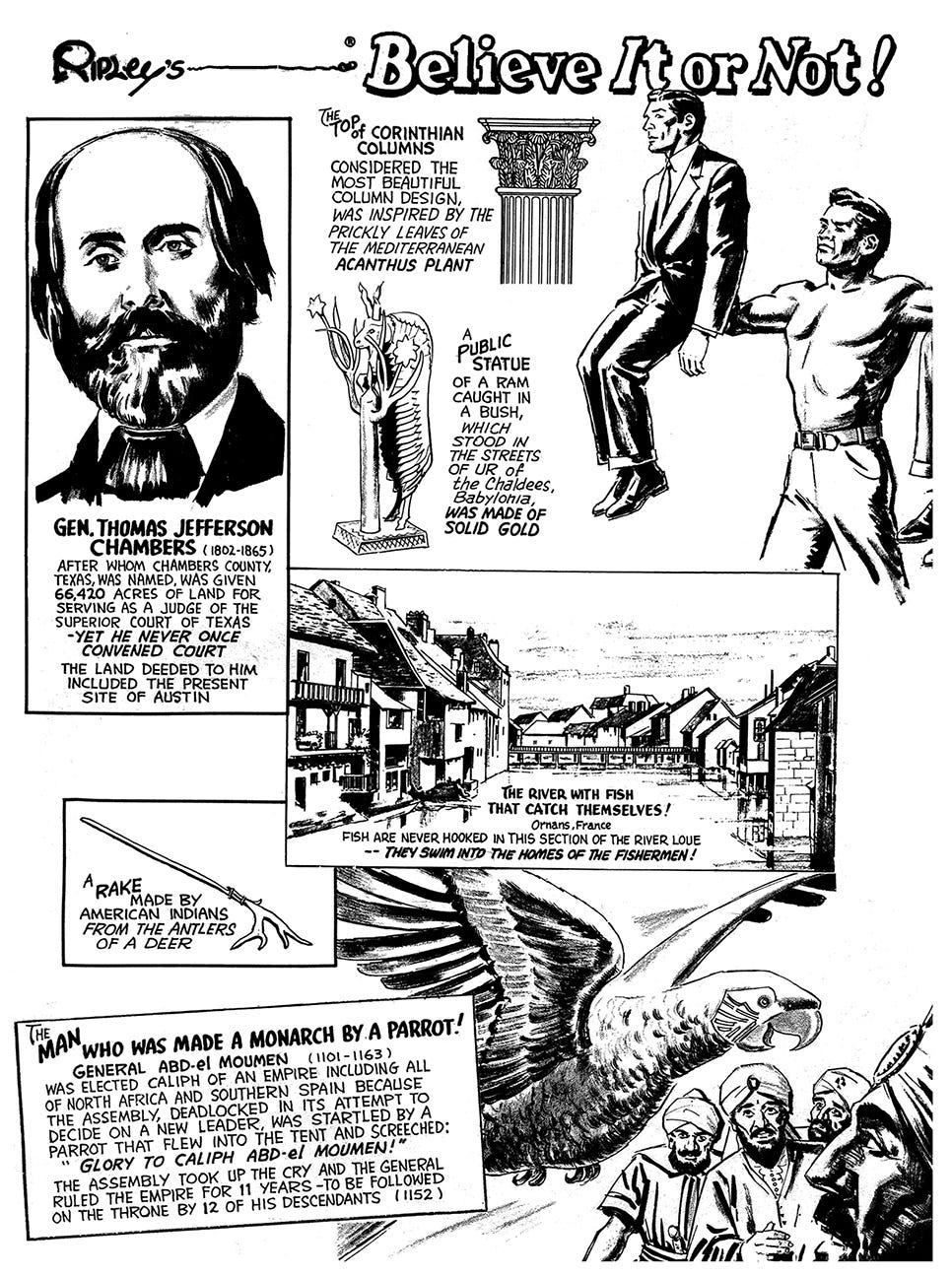

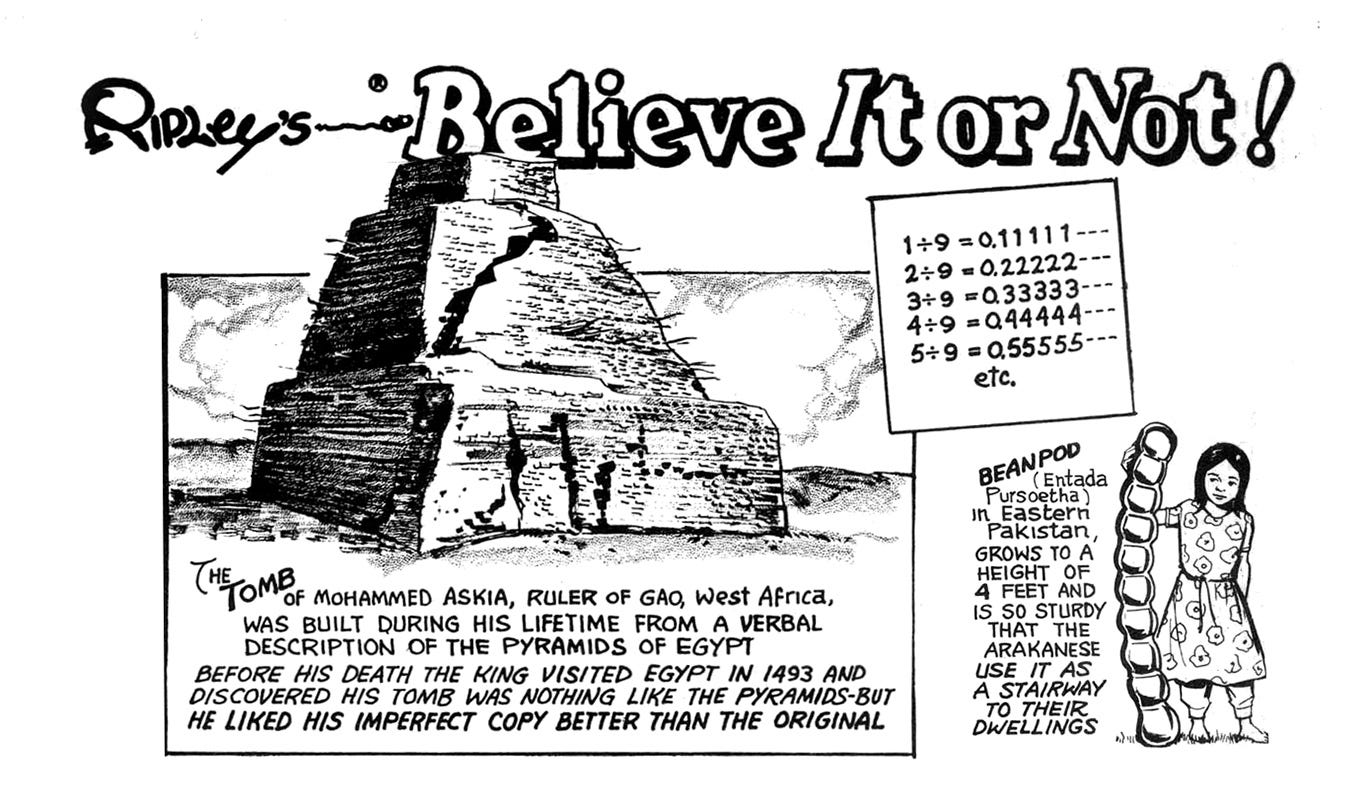

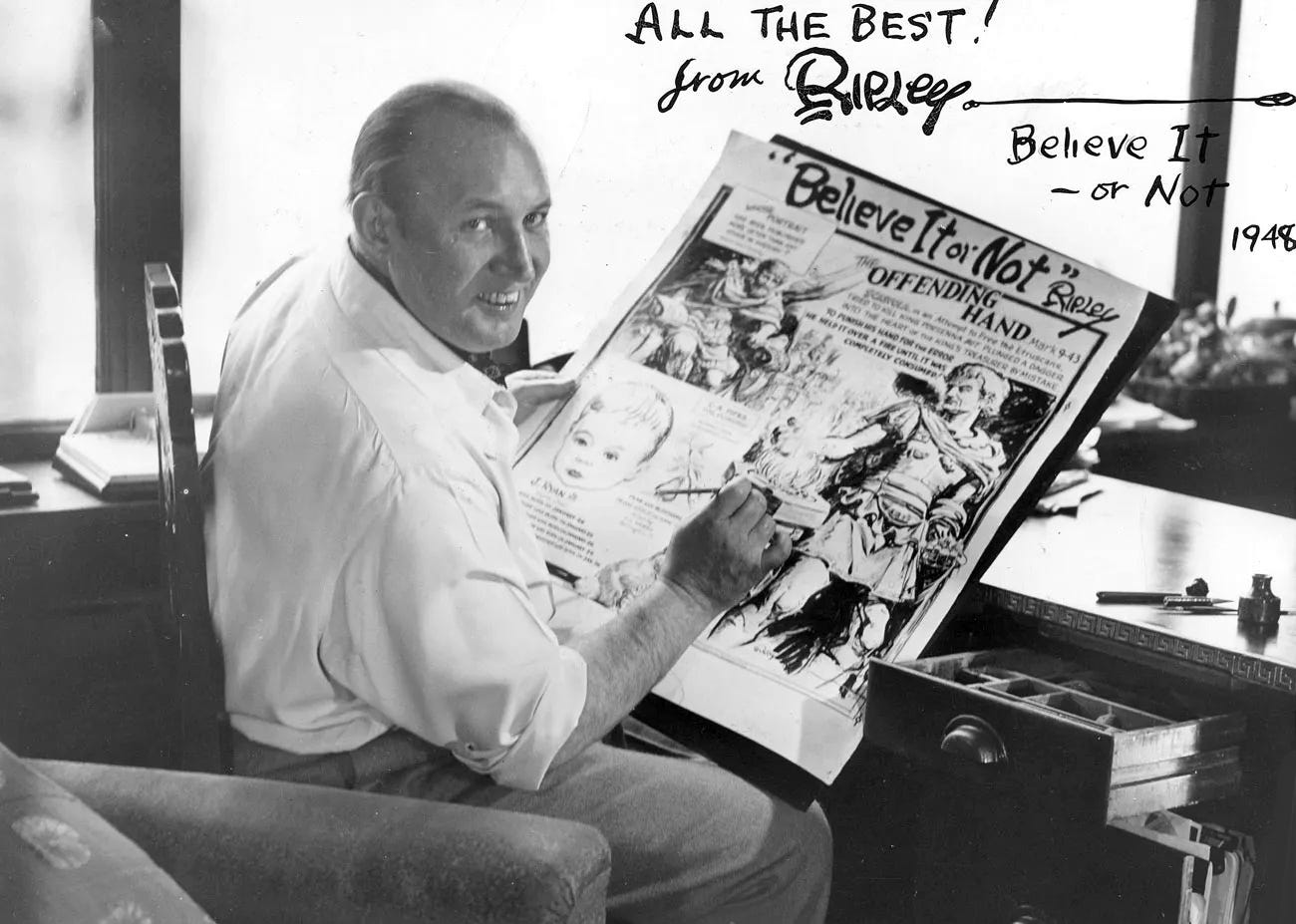

Robert Ripley (1890-1949) was an American cartoonist, amateur anthropologist and entrepreneur, who in the early 20th century created ‘Ripley’s Believe It or Not!’, an illustrated newspaper panel series, showcasing bizarre and fascinating facts from around the globe.

Born in Santa Rosa, California, Ripley was a shy, awkward child with prominent teeth and a skill at art. He contributed drawings to his high school newspaper and yearbook. In 1908, he sold a cartoon to Life magazine for $8. By 1909, he had secured a position as a sports cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle. During a 1910 boxing match in Reno, Nevada, he encountered the famed author Jack London who encouraged him to relocate to New York

In 1918 The New York Globe hired him as a staff artist and writer, where he created a cartoon featuring men performing extraordinary sports feats, including one man who held his breath underwater for six and a half minutes and another who walked backward across North America. A year later he produced similar cartoons with unique facts and special people, renaming the series ‘Believe It or Not!’.

Following a brief marriage to a young Ziegfeld Follies dancer, Ripley developed a deep passion for travel. In 1920, the newspaper assigned him to create some reportage of the Olympic Games in Belgium, and two years later he embarked on a global journey to craft a series of visual essays he titled ‘Ripley’s Ramble ’Round the World’. Ripley wrote and illustrated correspondence for the paper, capturing the sights and sounds of Japan, India, Italy, and other intriguing destinations, which were syndicated in numerous American newspapers that garnered a devoted readership, intrigued by the world’s mysteries.

By 1929, recognizing the popularity of his feature, William Randolph Hearst offered Ripley an annual salary of $100,000 to write and illustrate for his King Features syndicated newspapers.

Ripley wrote and illustrated informative factoids, bizarre sports feats and anthropological narratives from exotic places. He often featured submissions from small-town America, like oddly-shaped vegetables and two-headed animals. His belief was that the more unusual the better, like the shrunken heads he acquired from the Jivaro tribe of Ecuador. Readers mostly believed what he purported, yet often questioned his more eccentric claims.

Many of Ripley’s discoveries while traveling were initially uncovered by a research assistant in New York, who he hired in 1923 to scour the New York Public Library for intriguing tidbits that guided his travels. Ripley would often return with tangible proof of the wild wonders depicted in his cartoons.

By 1929, Ripley’s series boasted 80 million readers globally. Seeking broader horizons, he ventured into book publishing, film, radio, and odditoriums, the first of which opened at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. This strange museum showcased photos, props, illustrations, and live performances of astonishing acts, provoking reactions ranging from disbelief to outrage from its audience.

Ripley witnessed things that defied belief. He took photographs that he based his drawings on. In doing so (by publishing a drawing and not a photo), he brought his visual journalism into the realm of the imagination, which perhaps makes it less believable. With a photograph, there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist. Susan Sontag, in her essay in On Photography, writes that the photograph comes with ‘a bias of truth’. A drawing has no pretense. This uncertainty could be what Ripley wanted to elicit. It’s implied in the title, ‘Believe it or Not’.

Ripley wanted to be taken as authoritative. He once exhibited the Fiji Mermaid, a mummified creature that looked part monkey and part fish. It was once owned by showman P.T. Barnum, who described it as ‘an ugly dried-up, black-looking (sic) diminutive specimen, about 3 feet long. Its mouth was open, its tail turned over, and its arms thrown up, giving it the appearance of having died in great agony,’ Ripley exposed the hoax saying, ’Barnum was wrong. The public doesn’t like to be fooled. And I’m happy to say I’ve never fooled my public. Not that the public always thinks so.’What lessons can we learn from Robert Ripley’s career?

He captivated audiences with compelling compilations in word and image that resonated widely, skillfully tapping into the spirit of the times. He partnered with a powerful distribution platform. He encouraged the public to share their own stories. He expanded his brand into other media and venues, which provided him with a long career and substantial financial success.

Today, the megacorporation Ripley Entertainment continues to thrive with a variety of media offerings and an array of public attractions, including 28 Ripley’s Believe It or Not! odditoriums located around the globe.

All images and text © Ripley Entertainment Inc.

More to Know:

Robert Ripley may hold the record for the most mail received by a single person in history. View a small selection of his mail here.

Here’s more about the world of Robert Ripley.

Ripley’s Believe It or Not is the longest running syndicated cartoon in history. At least eight cartoonists have duplicated his art and writing style, and carried it forward. A new topical cartoon is published everyday.

Great post, Bill. I’m thinking that Odditoriums will be flourishing as long as there are humans to be amazed.

I loved "Believe It or Not" as a youngster, I grew increasingly doubtful about claims that were "sort of true," but exaggerated. Then I was given a copy of the Guinness Book of Superlatives (forerunner of the Guinness Book of Records), which was much better researched and therefore more reliable.

Nonetheless, Ripley's illustrations remain exciting, and often even thrilling.

BTW, the $100,000 that Hearst paid Ripley in 1929 would be $1.8 million in today's money.

CPI calculator: https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl